The Academy Awards recently announced their 10 picks for Best Picture. Naturally we had many thoughts about what was picked and what wasn’t. As with anything, the Academy gets it right some of the time and wrong some of the time. We at the Phoenix Critics Circle (PCC) got thinking about what are the best Best Picture winners of all time. We polled the circle and here is what we think are the ultimate times the Academy got the top honor right.

The Apartment - Nominated for 10 awards and winning 5, Billy Wilder’s classic tells the tale of Bud Baxter(Jack Lemmon) as he lends out his apartment to executives so they can have affairs and he can move up the corporate ladder. That is until he meets Fran (Shirley MacLaine).

Billy Wilder's story of love and longing, made in 1960, echoes with the same pathos felt in modern times. It's funny, charming, depressing, and romantic in all the right ways.

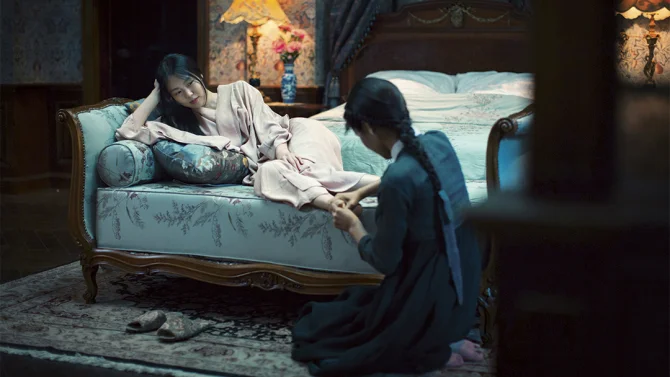

- Monte YazzieParasite - Of the six categories in which it was nominated for in 2020, Parasite won in four: Best Original Screenplay, Best International Film, Best Director, and Best Picture. It made history as the first Korean film to be nominated and win. The film follows the unemployed Kim family as they form a tense relationship with the wealthy Park family. Greed, class discrimination and familial trust is explored in this thrilling and unpredictable film.

A savage satire whose sting only grows sharper with time. - Josh SpiegelThe Silence of the Lambs -Jonathan Demme’s psychological horror thriller remains one of only six horror films that have been nominated for the category and the only to win it. The film stars Jodie Foster as Clarice Starling, a young FBI agent hunting the serial killer Buffalo Bill. In order to catch the killer, she seeks the advice of imprisoned serial killer Dr. Hannibal Lecter (Anthony Hopkins).

One of the most unconventional Best Picture wins in the Academy's history. Not only is it horror, it was released incredibly early in the year (February) - not great odds for taking the highest award. But it definitely made an impact, also picking up the coveted (and super rare) top five Oscars (Picture, Director, Screenplay, Actor, and Actress) - a feat only accomplished two other times in the Academy's history.- Mike MassieMoonlight - This 2016 film directed by Barry Jenkins is presented in three stages of life of the main character - his childhood, adolescence and early adult life. The film explores sexuality and identity. It is the first LGBTQ film, and notably with an all-black cast, to win the Oscar for Best Picture.

Small, tender, intimate - exactly the sort of film the Academy usually looks over. A milestone in Oscars diversity. - Barbara VanDenburghThe Godfather Part II - Francis Ford Coppola’s 1974 crime epic is the only sequel to win Best Picture. The Godfather won best picture as well. The film serves as both a prequel, following the rise of Vito Corleone (Robert DeNiro), and a sequel, tracing Michael Corleone (Al Pacino) as he protects the family business.

The rare sequel that is every bit as good as the original and some may argue is better. The duel storytelling, combining Michael and Vito’s experiences, paints a rich portrait of the immigrant experience in America. - Matthew Robinson