by The Massie Twins

Alien

In 1979, one of the greatest horror movies of all time could have been Prophecy - an environmentally-conscious thriller from veritable, veteran, master-of-suspense director John Frankenheimer (the man behind the pulse-pounding The Manchurian Candidate (1962) and sci-fi noir Seconds (1966)). But instead, because its plot was slow, meandering, and unfocused; its set designs were uninspired, incomplex, and simply not scary; and its monster effects were shoddy (the gawky, killer bear-thing mustered chuckles rather than screams), a different picture from 1979 took the opportunity to make its mark.

Ridley Scott’s Alien was, in many ways, set to fail in the same fantastic fashion in which Jaws could have collapsed under its own ambitions just four years earlier. From a director who was still learning the ropes to an ungainly, titular antagonist that malfunctioned regularly, Alien could have been a bumbling disaster - much like Prophecy. But in the acting, the environments, the photography, the sound, the tone of the film, the editing, and certainly the visual effects, Alien managed, perhaps miraculously, to look impeccable; everything somehow came out all right.

"You know, Sigourney, it’s better if you don’t look in the camera," the then 28-year-old actress was brusquely told by Ridley Scott, who himself had only one film to his name. Incredibly, the role was also originally written for a man. But this unlikely heroine became so striking, particularly with the earnest way in which she responded to all of the harrowing scenarios (Ridley purposely kept the alien components hidden from the crew, as much as possible, so that their reactions would be genuine), that she would remain the one true constant between three theatrical sequels.

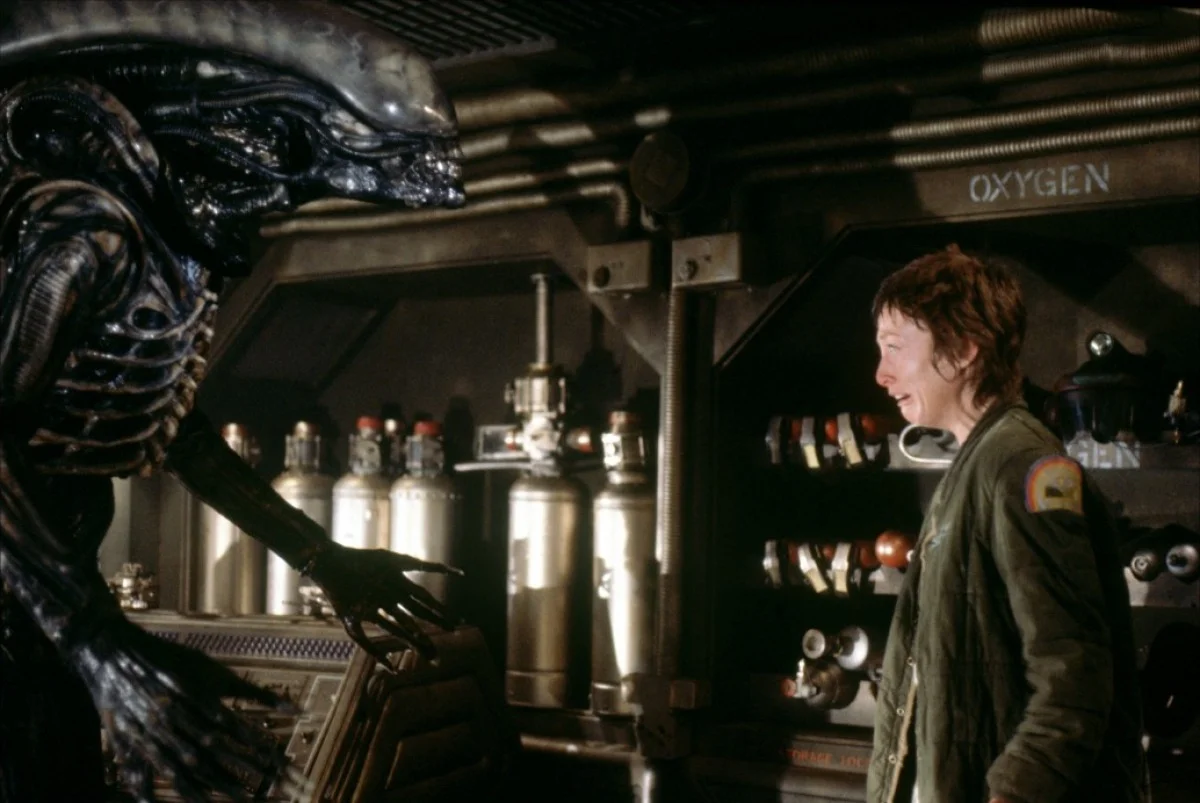

"As soon as you accept a script like this, you begin to worry about what you’re going to do with the man in the rubber suit," said Scott, just as pre-production got underway, addressing a fear - and a failure - that became unfortunately realized by Frankenheimer’s Prophecy. Swiss surrealist H.R. Giger saved the day for Alien (despite being dismissed at one point by the producers, who thought his early concepts were far too repugnant) with his grotesquely erotic creature designs, crafted primarily from an existing painting entitled Necronom IV. Not only did Giger invent the alien itself, he also contributed to the derelict ship, the fossilized space jockey prop (a towering, 24-foot, behemoth sculpture), the uninhabitable planet, and the egg/facehugger combo (which was deemed so inappropriately vagina-like that the single-slit opening was censored/edited into a cross shape - much to Giger’s amusement, as one vagina essentially became two). It’s also difficult to dismiss the uncomfortably obscene nature of the facehugger, which commits oral rape to impregnate its victim, and the phallic shape of the chestburster, which mirrors the adult version’s cranium. "Giger did this black cockroach from hell," mused concept artist Ron Cobb. "When you saw the suit standing in this little bay where Giger was sculpting it, you would actually flinch when you walked in the room. It was really terrifying."

The story might not be the most original: a crew of seven are slowly picked off one-by-one in a haunted house in space (many critics of the time even likened several specifics to Mario Bava’s Planet of the Vampires (1965), which did conspicuously feature an oversized, mummified humanoid in a dilapidated ship). But if ever there was a film to take such a practiced premise and radically upend it through alarmingly advanced visuals, it was this one. From its claustrophobic, labyrinthine spaceship corridors, to the otherworldly, windswept planet, to the obvious set pieces of gore and mutilative attacks, Alien is very much a movie of significant, unforgettable, horrifying frames, hauntingly strung together to maximum effect. Although, upon its release, many of the more gruesome set pieces (primarily the chestburster sequence) would become emphases of conversation, the structuring of these moments is nothing short of archetypal. Perhaps what makes it all work together so well is that every second is handled with the utmost sincerity and severity; comic relief is virtually nonexistent and the cast members take their parts completely seriously.

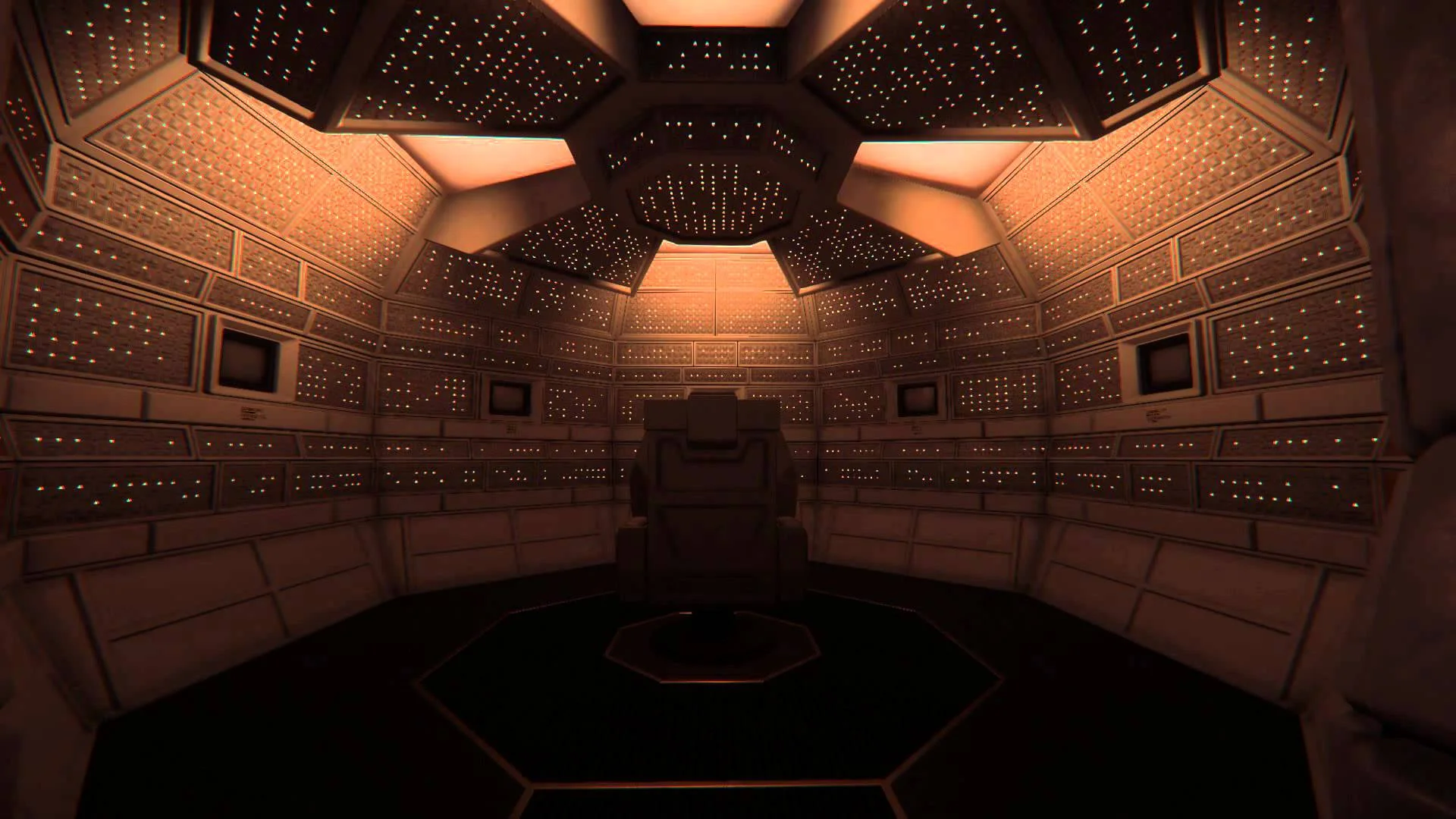

The little details are also spectacularly winning: the casual, believable small talk between space truckers, mostly focused on monetary incentives; the Mother interface room, glittering with patterns of lights that are just off-putting enough to distract from the outdated computers themselves; and, of course, the macabrely hypnotizing, convoluted, biomechanical layouts of Giger's artwork come to life. Humidity also plays a prominent role as one of the most notable of the minor details (something elementary yet effective, which doesn’t find its way into enough low-budget pictures): oxygen/carbon dioxide is emitted from spacesuits and venting apparatuses in the form of heavy steam; obnubilating fog tumbles across the alien planet’s surface; the floors and walls of the derelict ship glisten with rigid beads of moisture; at some point, every character sweats indiscreetly; and the monster itself is so overloaded with viscid fluids that it salivates continuously.

The fact that the hapless explorers are commercial mining employees and not experienced archeologists or military rescuers, is also brilliant - as is the order in which the characters are dispatched, starting off with some of the more confident decision-makers and superiors in the chain of command. This ties into the use of problems that arise outside of the monster itself (an evil company unconcerned with safety protocols; unexpected betrayals; damage to the ship; faulty lights; and a lack of adequate weaponry) - a tactic employed by many of the best horror films of the era. Jump-scares also make an appearance, along with familiar but dependable gimmicks - like the graininess of camera feeds and the cutting out of video and sound during the planet's investigation, loudly knocking over a random item, or a blaring self-destruct clarion. Jerry Goldsmith's music must also be mentioned (it contains some nicely unforeseen, playful notes), along with the script’s superb use of foreshadowing (dialogue such as ...like he exploded from inside, and If we break quarantine, we could all die; the discovery of molted skin; and a deviously suspenseful motion-tracking device).

Aliens

Taking an astonishingly long time (especially by Hollywood standards) to churn out a sequel, James Cameron's Aliens (1986) would prove to be worth the wait. The tone and style shifted dramatically, as Cameron’s vision become something of a war-torn, Vietnam-like battleground of ill-preparedness (with platoons being outgunned and outmanned) in a hostile, foreign terrain, amplified by equal helpings of cockiness and skepticism. In this direct follow-up, plenty of time has passed, but the threat is chillingly familiar. Graduating from a single, confined location to a far vaster array of tunnels, sub-levels, vehicles, docking bays, and medical centers - and increasing the enemy from a lone infiltrator to an organized, established colony of more than a hundred - Aliens aimed to expand upon nearly every premise touched upon in the original. And it also added a pronounced amount of high-octane adventure, giving this entry in the franchise the rare distinction of being an action movie just as much as a horror film.

The alien eggs are more elaborate, gooier, and reveal more striking hints of the scorpion hellion buried beneath organ-like sacs of fluid. The facehugger, which was formerly a stiff, rubbery carcass after its throat-violating mission was accomplished, has become a spidery, lightning-fast assailant that lunges from lofty perches or scurries across floors on bony fingers. The chestburster now possesses arms and a greater range of movements, all while its entrance boasts inflated unease with the combination of a female victim who begs for a swift mercy-killing, more dismaying sound effects, and the body-horror of binding organic secretions. And the adult drones are now plentiful and flexuous, shot with altered frame rates to generate eerie, insectoid movements and behaviors. If all of these exaggerations in the xenomorph (a term coined for use on these singular extraterrestrials) life cycle wasn’t impressive enough, Cameron also designed a mother alien to lead her brood. Based on paintings by the director himself, legendary effects wizard Stan Winston crafted the imposing monstrosity (a marvel of animatronics and slime) that would be dubbed the "Alien Queen", which contributed to an epic showdown between the universe’s toughest female fighters. Lesser components are also conceptually escalated, including a motion-tracking device, an android revelation, and the motives of the deviously omniscient Company. It would seem that Aliens took everything to the next level - a level so high that future iterations had no where left to go (as painfully evidenced by Alien 3 and Alien: Resurrection).

What these two seminal sci-fi masterpieces ushered in was a slew of derivations and rip-offs that plagued the ‘80s and ‘90s. But if an aspiring filmmaker was to copy another artist’s work, there really is no better place to start than with Alien and Aliens. The list of films that drew inspiration from these sources is virtually endless. Among them are wholly watchable, entertaining B-movies, as well as mediocre efforts and downright laughable works of plagiarism. Some of the better attempts include projects like Deepstar Six (1989), The Terror Within (1989), Leviathan (1989), Species (1995), Mimic (1997), Virus (1999), and even Life (2017). The tawdrier ventures include Parasite (1982), Contamination (1982), Xtro (1982), Biohazard (1985), Creature (1985), Syngenor (1990), Screamers (1995), Pandorum (2009), and Splice (2010). But, by far, the most despicable, contemptible, trashiest imitation of Scott and Cameron’s contributions to the genre is Alien 3000.

Alien 3000

If Alien is the ultimate haunted-house-in-space picture, and Aliens is the apex of action and horror united (and the epitome of an anti-space-opera), Alien 3000 is the absolute worst of each of those ideas combined. If it wasn’t bad enough that the movie is virtually irredeemable in its shabbiness, the advertising for it is something altogether, differently reprehensible. The DVD cover art actually depicts a creature from the wrong movie (it's from the 1997 film Breeders) and, unfortunately, it never makes even a guest appearance in this one. There's also not a single reference to the year 3000. This just might be the single most disastrous exploitation of the Alien legacy ever made. Despite countless derivations produced up to this point (it was released in 2004), and countless others manufactured afterwards, Alien 3000 is so bad that its dreadfulness just might never be topped.

The title graphics are oddly reminiscent of Alien: Resurrection, with glowing green text and glimpses of the model used for the starring abomination - which is so pitifully designed that it isn't even as articulated as a child's toy. The film then opens on a peeping tom with binoculars spying on a couple as they make out (he cringingly uses the phrase "little jack rabbits" as slang for the woman's exposed breasts). The three of them are actually all part of the same group, studying seismic readings in the area. When a 6.0 quake opens up a cavern in the side of a mountain, the threesome venture inside to discover ancient gold artifacts (including conquistador-like swords encrusted with rubies) and ominous shadows moving around in the back of the cave. Of course, the first creature to emerge is a tiny bat, scaring the shapely blonde - before a much larger, nearly invisible humanoid (very much like a Predator) swiftly decapitates her.

But it's all part of a nightmare, revealing that lone survivor Katie Simmons (Megan Malloy) - from a previous attack that unfolded identically to the opening scene - is plagued by graphic visions during her incarceration at the Thorton Psychiatric Clinic (a set that never gets more intricate than an apartment kitchen). When a park ranger stumbles upon the dead bodies of the hikers in real life, it's up to the Bureau of Paranormal Research to get to the bottom of it. Katie is then visited by BPR agents (technically called detectives from the Office of Paranormal Investigations), to whom she reveals that the brutal slayings are somehow connected to the cursed treasure in the cave - and that her precognitive abilities are linked to the mysterious monster. Somewhere along the line, the government hires mercenaries, led by Sergeant McCool (Christopher Irwin), to explore the cavern and, if possible, to capture the anathema.

The head of the BPR, Sheila (played by Priscilla Barnes), can't seem to deliver her dialogue clearly - perhaps because she refuses to remove the eraser-end of a pencil from between her lips. "I understand. I do have a Ph.D. in psychiatry," retorts lead investigator Carla (Shilo May), outlining what the filmmakers believe to be necessary verbiage for character development. The remainder of the supporting roles are counterparts for the Colonial Marines from Aliens - from the tough female fighter; to the cocky, expletive-spewing soldiers; to the calmer, controlled commander. One guy does nothing but sharpen his knife on a whetstone; another totes a paintball bazooka for anticipated downtime; and one of the indistinguishable troopers likes to spit or chew on a cigar.

The production is extremely low-budget, sporting all the trademarks of prohibitively limited resources and hasty filmmaking. The actors are terrible (Lorenzo Lamas, who takes top billing, appears for a couple of minutes and then vanishes, only to reappear for very brief additional sequences - wherein he does little more than pose with his shotgun or a pirate sword; he's very much a Z-grade action star in the first place, here also serving as an associate producer); footage is reused; the ADR is considerably off; the costumes and armory are all unmatched or misshapen; the soldiers' rations are just granola bars; and the mercenaries never go any deeper into the cavern than the entrance (presumably because the budget couldn’t accommodate an additional set). One of the characters even calls his companion by the wrong name, while another moment shows the exchange of hand signals - and then the spoken line, Did you see that? which, of course, negates the need for hand signals. To further make a mockery of all things sci-fi and horror, Alien 3000 includes panicky conversations getting broken up by the more level-headed members; weapons being dramatically loaded with ammunition; an unglamorous, comical sex scene; specialist Phoebe (Phoebe Dollar) cheering on the alien as it attacks a deserter; and Kate continually awaking from nightmares, screaming directly at the camera, on no less than six separate occasions.

Additionally stealing from Aliens, the characters must wait for a helicopter to return to pick them up (a dust-off), only to realize that the creature has climbed aboard, resulting in the vehicle's destruction; motion-trackers that have blips for movement (though they don't actually move) are hefted; there’s a suicide by grenade; and a military march plays subtly in the background. The movie even proceeds to defraud Independence Day, with an alien who communicates through the vocal cords of its human victim, and Predator, through the use of an invisibility cloak, infrared imagery for the monster's visual perspective, and green blood. And there are also sporadic flashbacks to an entirely different movie, which is never explained. However, this becomes clearer to anyone aware of the fact that Alien 3000 was previously released as Unseen Evil 2 (a loose sequel to the equally deplorable Unseen Evil from 2001, which was itself also released under the title The Unbelievable). In the case of this exceedingly shabby filmic endeavor, it would be far wiser to simply re-watch the aforementioned 1979 and 1986 contemporary classics; sometimes, it’s just not gratifying to seek out obscure copycats of beloved masterpieces. One can only hope that Ridley Scott’s 2017 film Alien: Covenant - his first official prequel to use the title Alien - can redeem (or perhaps erase) the plenitude of pitiable attempts at recreating the awe of his 1979 magnum opus.