by Jeff Mitchell

Tumble out of bed, and I stumble to the kitchen. Pour myself a cup of ambition and yawn and stretch and try to come to life. Jump in the shower, and the blood starts pumping. Out on the street, the traffic starts jumping with folks like me on the job from 9 to 5.

- “9 to 5” by Dolly Parton

Ms. Parton’s lyrics - from her 1980 hit song - should ring true for just about anyone who has grabbed their lunch pail, left their residence and clocked into work. Of course, in 2017, the way we work has changed. Metal, oblong lunch pails are generally devices of the past. Instead of driving 45 minutes in rush hour traffic, some employees log into their PCs from a home office, kitchen table or coffee shop. One could easily name about another three dozen work evolutions, but with more competing demands pulling on the average 21st century adult, the 9am to 5pm workday has transformed.

The aforementioned 8-hour workday might break down into a bizarre 10-hour shift of: 7am to 10am, 12pm to 4pm, and 7pm to 10pm. And with the service industry job explosion and new global workplaces, early mornings, late evenings, weekends, and holidays are not necessarily off-limits either. (Wow, what would Fred Flintstone think?) The point is that work composes a significant portion of our waking hours, and since movies can reflect our lives, the workplace plays a sizable role in the world of cinema too.

Now, just about any movie - outside of My Dinner with Andre (1981) or 127 Hours (2010) – features someone earning a living in some capacity, but here are some notable films from several genres that center around the workplace.

Blue-collar work

Outside of the comfort of temporary walls, break rooms, air-conditioning, and coworker birthday celebrations, blue-collar movie-heroes put in an honest, hard day’s work for a day’s pay. Their bosses, however, may not view the world with the same sense of fair play. The average employee sometimes fights uphill battles.

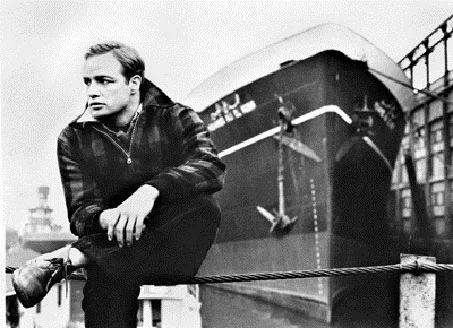

One of the best movie-examples of this is On the Waterfront (1954). Terry Malloy (Marlon Brando) knows something about fighting, because this ex-boxer – turned longshoreman - battles Johnny Friendly’s (Lee J. Cobb) operation at the Local 374. Johnny is rolling in dough, but the men earn a mere pittance while unloading pallets of bananas or Irish whiskey from a constant stream of incoming ships for long, long hours. In Brando’s iconic, Oscar-winning performance, he brings a sincere and endearing humanity to Terry, who takes a stance against inequitable conditions. He stands up for what is just, even when he feels personally inequitable. He believes that he “earned a one-way ticket to Palookaville” and “could have been a contender”, but we know that Terry is certainly more than an ordinary contender.

Whether or not one agrees with his politics, there is no denying that Oscar winner Michael Moore stands up for the little guy. Moore won the Best Documentary Oscar for Bowling for Columbine (2002), but his movie career started with the groundbreaking, matter-of-fact documentary, Roger & Me (1989). Growing up in Flint, Mich., Moore watched as General Motors closed nearby factories, so he decided to grab a camera and confront GM CEO Roger Smith. Twenty-eight years later, actions like GM’s have repeated in every state in the union, but hey, Moore did warn us.

Working behind the register of a New Jersey convenience store would appear to be a stress-free job, but no one warned Dante Hicks (Brian O’Halloran) about his upcoming day in Clerks (1994). In director Kevin Smith’s absolutely hilarious first feature – filmed in black and white on a shoestring budget – Dante deals with a constant stream of oddballs looking to buy cigarettes, candy and milk, while his ex-girlfriend drops by and two harmless drug dealers loiter outside. Highly conversational, Smith’s picture paints the struggles of directionless 20-year-olds, as Dante and his best friend, Randal (Jeff Anderson), opine about the original Star Wars trilogy and pornography and also plan a street hockey adventure. No, Dante’s work is not overly laborious, but he was “not even supposed to be here today.”

Honorable mentions:

Silkwood (1983), Driving Miss Daisy (1989) and Men at Work (1990), but only because it has the word “work” in the title.

Downsizing

Although office employees do not endure physically strenuous roles, modern-day corporate environments certainly provide their own forms of duress. Office Space (1999) is the most frequently quoted and referenced film of the last 18 years that wonderfully captures carpet dwellers’ ecosystems, and rightfully so. In addition to looking for staplers and producing TPS reports, downsizing rears its cost-cutting head in the picture as well, and that practice has been a staple for many movies over the years.

In Up in the Air (2009), Ryan Bingham (George Clooney) has spent years firing people, and in fact, he has built his career around it. Spending most of his waking hours flying to various locales, he gives unlucky employees their walking papers with a humane, but firm hand. With so much experience in delivering horrible messages, he has developed a panache for offering advice to outgoing worker bees. In one particular scene, he suggests to Bob (J.K. Simmons), a frustrated middle manager, to perhaps pursue his dreams in the culinary arts. Bob absorbs the message but realizes that he will only pull in $250 a month in unemployment while chasing this aspiration.

Bob may eventually accept his fate, but William Foster (Michael Douglas) in Falling Down (1993) takes an altogether different approach. Let go from his defense contract job and stuck on a Los Angeles roadway, William leaves his car and walks across the city sporting a short-sleeve white-collar shirt, a tie and glasses last seen in a 1950’s elementary school classroom. He is angry about his losing his job, losing his wife in a divorce and now he begins losing his temper during encounters with his fellow Southern Californians during a stifling hot day. His sense of purpose is lost, and his journey in this urban minefield offers a highly metaphorical experience for the viewer.

In Two Days, One Night (2014), Sandra (Marion Cotillard) copes with two figurative minefields as well. She is taking a temporary leave of absence from her job at a Belgian solar panel company due to depression and anxiety, but management might permanently remove her from the company payroll in order to cut expenses. Actually, management offers other employees a choice: keep your bonus or keep Sandra employed. In a truly fascinating look at the human condition, Sandra approaches each of her coworkers over a weekend to ask for their vote of confidence, and her colleagues respond in various – heartbreaking and sobering – ways. The Academy rightfully nominated Cotillard for a Best Actress Oscar, as she masterfully captures the internal churn of potentially losing one’s job, while her character attempts to discover her self-worth.

Honorable mention:

Glengarry Glen Ross (1992)

THE Working Man – Michael Keaton

Tim Burton raised a few eyebrows by tapping Michael Keaton for the role of the Caped Crusader in Batman (1989), but the Beetlejuice (1988) star donned a black suit, mask and cape and successfully delivered critical and box office praise with a serious, brooding persona not seen by Adam West’s version of the character. In the end, casting Keaton’s no-nonsense approach made perfect sense, and this Pittsburgh native has enjoyed a career by playing industrious men.

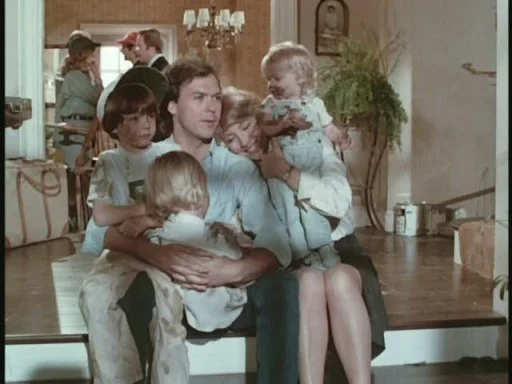

In Mr. Mom (1983), Keaton’s character, Jack Butler, actually loses his job at an auto plant and switches daytime roles with his wife, Caroline (Teri Garr). Jack becomes a stay-at-home dad, while Caroline gets a job to support their family, and Keaton serves up about one thousand quotable lines in this memorable comedy written by John Hughes (e.g. “Yea, 220, 221. Whatever it takes.”). Admittedly, the film loses steam in the last act once Jack gets it together at home, but not before he hilariously struggles with shopping, changing diapers, operating several household appliances, and more.

Three years later, Keaton starred in Ron Howard’s Gung Ho (1986), and this comedy confronts cultural differences between the U.S. and Japan. A Japanese auto company buys a closed Pennsylvania auto plant and attempts to introduce efficiencies not practiced in America. Keaton’s Hunt Stevenson is a slightly bolder, crasser version of Jack Butler, who would make a great weekend-softball team captain, when he is not tirelessly attempting to turnaround the plant’s fortunes.

Keaton traded in auto company work for the newspaper biz in a pair of very notable films. Ron Howard signed on Keaton again in The Paper (1994), and the film captures the tension between financial pressures of the industry with journalistic values, and the opposing views are championed by Glenn Close and Keaton’s characters, respectively. Howard juggles several intriguing plotlines with an all-star cast including, Robert Duvall, Marisa Tomei, Jason Robards, and Catherine O’Hara, but the movie’s lifeline comes down to a war of wills between Alicia (Close) and Henry (Keaton).

Whether or not director Tom McCarthy saw Keaton play the city editor in The Paper, he made a master stroke in casting Michael in his Best Picture Oscar-winning film Spotlight (2015). Keaton plays Robby Robinson, who leads The Boston Globe’s Spotlight team. A small, tightknit group of journalists, the team deeply dives into lengthy investigations, ones which absolutely need plenty of time, space and resources to find resolution. Spotlight recreates the Globe’s efforts in uncovering extensive child sexual abuse by Catholic priests in the greater Boston area, and Keaton’s Robinson presents a steady hand and support for his journalists (Mark Ruffalo, Rachel McAdams and Brian d’Arcy James).

Spotlight is one of four terrific films that Keaton has enjoyed during his recent comeback. Birdman or (The Unexpected Virtue of Ignorance) (2014), The Founder (2016) and Spider-Man: Homecoming (2017) are the others, and naturally, he plays hardworking entrepreneurs in these movies as well. Who knows if Keaton is the hardest working man in show business, but he might be the king of contemporary working men on the big screen.

Women in the Workplace

In 2017, one of America’s great mysteries is that women still do not earn as much as men. Depending upon the study, one might find that the average woman earns 70 to 90 percent of a typical man’s wages. Not only do women continue to fight for equal pay, but treatment too, and these campaigns have been reflected on the big screen.

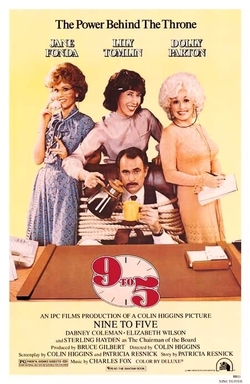

Commercially, no other film resonated with the public more than 9 to 5 (1980). It was the second highest grossing film that year ($103 million and second only to The Empire Strikes Back), and it addressed an unfair workplace for women in a comedic and empowering way. Judy (Jane Fonda), Violet (Lily Tomlin) and Doralee (Dolly Parton) plot against their boss, Franklin Hart (Dabney Coleman), after his repeated sexist slights in the office for years. The three wind up running the company, while keeping Mr. Hart indisposed in a most bizarre way. All three leads are especially good and very likable, and Fonda offers the biggest surprise with her understated performance. Arriving in theatres during the height of the women’s movement, the film – and Parton’s song - struck a chord with audiences, especially with women who were impacted by discriminating office environments in their own lives. One can imagine packed 1980 movie theatres bursting out in laugher and emotional release when Doralee threatens Mr. Hart by saying, “I’m gonna get that gun of mine and change you from a rooster to a hen in one shot.”

For Josey Aimes (Charlize Theron), she feels like she is trapped in a hen house with packs of aggressive wolves within her place of work, a local Minnesota mine. In North Country (2005), this single mom has no other way to support her two kids and realizes that the work would be demanding but had no idea that she would become the victim of an avalanche of sexual harassment and emotional/physical abuse within a male-dominated environment. From the beginning of her daily shift, Josey and other women live a nightmare, and while watching this movie (taking place in 1989 and based on a true story), it absolutely makes one sick that this type of chauvinism existed just 28 years ago. Somehow, Josey wills the strength to face seemingly impossible odds while toiling with her own vulnerabilities. Theron and Frances McDormand rightfully earned Oscar nominations for Best Actress and Best Supporting Actress, respectively.

Speaking of Oscars and McDormand, she and Sally Field won Best Actress Oscars for playing strong women in the workplace. In Fargo (1996), Brainerd Police Chief Marge Gunderson (McDormand) – carrying a folksy persona and a future baby (as she is very pregnant) – pulls all the right strings to untangle a kidnapping plot. Chief Gunderson is the smartest person in every room, and her calm and temperate approach to crime fighting proves just as effective as forceful police roles that audiences are used to seeing.

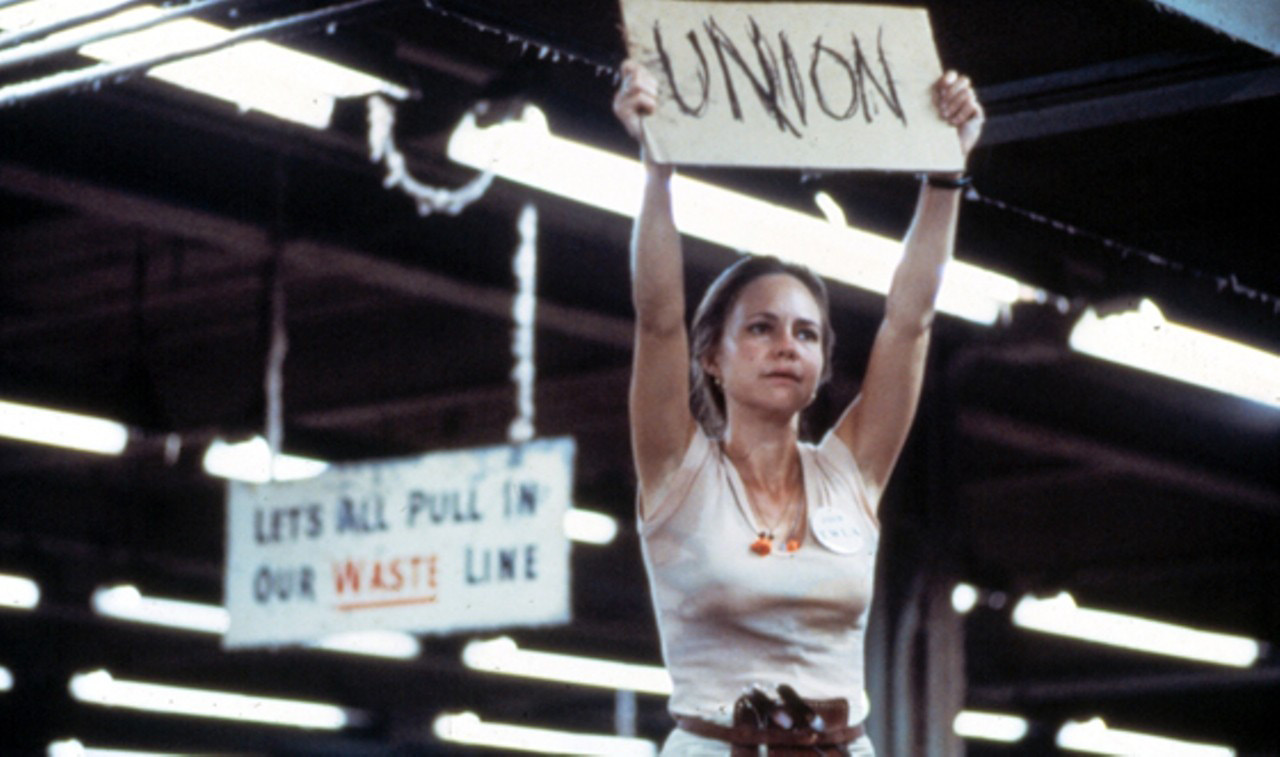

Field captured her first Best Actress Oscar with Norma Rae (1979) by playing the title role. Like the female-trifecta in “9 to 5” and Josey in North Country, Norma clashes with the system too. She works in a North Carolina cotton factory, but rather than fight for female rights, she stands up for all the workers against unfair conditions. Defiant and altruistic in her beliefs, Norma is a leader, and the words “stand up” can be taken literally and figuratively in the picture. When she raises a sign (with “UNION” written on it) above her head, every pair of eyes - on-screen and in the audience - become completely focused on her.

Honorable mentions:

Holly Hunter in Broadcast News (1987), Melanie Griffith in Working Girl (1988), Hillary Swank in Million Dollar Baby (2003), and Taraji P. Henson, Octavia Spencer and Janelle Monae in Hidden Figures (2016)

Government Bureaucracy

According to a June 23, 2015 Forbes.com article, Walmart and McDonalds employ 2.1 and 1.9 million people, respectively, and although this business publication does not list Starbucks, drive five miles from your home in any direction, and one might conclude that this mammoth coffee house cannot be far behind, right? Perhaps Starbucks skyrockets to 5 million employees during pumpkin spice season, but I digress. Walmart may have cornered the market on worker bees in the private sector, but yes, the government is the world’s largest employer. In fact, the same article stated that the U.S. Department of Defense provides jobs for 2.3 million people.

Over the years, movie houses have filled theatre seats with films about the government, and Frank Capra’s Mr. Smith Goes to Washington (1939) particularly stands out. Now, politics has become a figurative combat sport in recent months, but after watching this Jimmy Stewart classic, one realizes that the fight has endured for decades and decades. Jefferson Smith (Stewart) is a brand new senator and arrives in D.C. with a squeaky clean image, as a colleague tells him, “This is no place for you. You are halfway decent.”

This movie certainly is leaps and bounds above decent, as Capra engineers a timeless David vs. Goliath film. Senator Smith does not even own a slingshot, but his inspiring principles certainly aim true.

Director Stanley Kubrick aimed true and landed on target with his wild, weird, unsettling, and hilarious dark comedy, Dr. Strangelove or: How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb (1964). Peter Sellers plays the President of the United States (and two other roles, including the infamous Dr. Strangelove) and is joined by an extensive cast, whose characters are hunkered down in a war room trying to prevent a nuclear strike on the Soviet Union. Kubrick, Terry Southern and Peter George scribe a bureaucratic mess in which phone calls and side meetings emerge as fairly useless, because red tape and regulations did not account for one of its base commanders going “a little funny in the head” and ordering a strike on the U.S.S.R.

Dr. Strangelove, of course, contains one of the most iconic images in cinema with Maj. King Kong (Slim Pickens) riding a nuclear bomb like a horse and waiving a cowboy hat in fulfilling a morbid date with destiny. As satirical as Strangelove feels, another film arrived in theatres that same year with a similar premise, but with much bleaker tones.

Director Sidney Lumet’s Fail-Safe (1964) - a deadly-serious picture with a Twilight Zone-feel - features U.S. military leaders desperately trying to call back six bombers from unleashing a nuclear assault on the U.S.S.R. The President of the United States (Henry Fonda) attempts to avert the crisis, and everything hinges on his call with the Soviets. Men with lots of stripes and badges litter the screen, but they also work in shadows. Within the confines of sterile control rooms and office spaces, Lumet often places various scenes within real shadows that symbolize the ironic practice of protecting American lives by actively participating in military buildups. In one particular frightening conversation, one argues that 60 million Americans killed in a nuclear attack is significantly better than 100 million. Fail-Safe may not be a pleasant trip to the movies, but it stands as one of the most frightening thrillers in cinema and a perfect companion piece with Strangelove.

Honorable mention:

No Way Out (1987), Lincoln (2012) and I, Daniel Blake (2016)

Work Should be an Adventure

These films about blue-collar jobs, downsizing stress, women in leadership roles, government bureaucracy, and a few others starring Michael Keaton are all centered around the workplace. These cinematic gems, however, do not offer arduous experiences for the viewer, but tales of caution (Fail-Safe) or celebration (9 to 5). Certainly movies can be wondrous escapes from reality, but catching a movie about real life – and in this case, a film in which its lead protagonists clock into the office for a full workday – can be just as rewarding…and/or inspiring.

For anyone who has wanted a career change, watch the quirky, bizarre but highly inventive Joe Versus the Volcano (1990), in which Joe (Tom Hanks) quits his downright awful job in a dim, dank office and launches into a most unexpected, colorful adventure. Movies can be a reflection of our lives, and since life should be an adventure, that includes our time between 9 to 5. The next morning that you “tumble out of bed and stumble to the kitchen” in preparation for the workday, I hope that you are sporting an authentic smile or formulating a plan to eventually get one. It’s not impossible. It’ll just take a little bit of work.

Jeff – a member of the Phoenix Critics Circle – has penned film reviews since 2008 and graduated from ASU’s Walter Cronkite School of Journalism. Follow Jeff and the Phoenix Film Festival on Twitter @MitchFilmCritic and @PhoenixFilmFest.