by Josh Spiegel

With few exceptions, the last 25 years have created familiar patterns for cinephiles and Oscar watchers. The first few months of a given year are usually full of unremarkable releases from studios simply trying to clear up their slate for the later months. The summer season is home to the biggest blockbusters that Hollywood has to offer. And then there’s the fall, when the prestige pictures get the spotlight, as both big and small distributors angle to get a spot at the table when the Oscars, Golden Globes, industry guilds, and critics’ groups (such as the Phoenix Critics Circle) give out awards.

In the last couple of years, some aspects of these patterns have shifted, but largely those revised patterns only shifted what constitutes the summer movie season. Big-budget blockbusters that previously would have been released only in June, July, or August now get released as early as April (such as this year’s The Fate of the Furious) or as late as December (a little film called Star Wars: The Last Jedi, for example). As of this writing, the highest-grossing film of 2017, Disney’s live-action remake of Beauty and the Beast, was released in mid-March, not around Independence Day or sometime during the hotter months of the year.

The Prestige Movie Season

But while the summer movie season now extends to almost the entire year (though studios still basically avoid releasing big movies in January and August), the season of prestige pictures is still largely focused on the final three months of the year. Since 1990, only six Best Picture winners at the Oscars were released before September, with The Silence of the Lambs opening in theaters in February of 1991 and winning the gold statue more than a full year later. In addition, within the last 15 years, just Best Picture winners were released in the early part of their respective release years: Crash and The Hurt Locker. Otherwise, the Best Picture winners, as well as many other nominees, go down the festival circuit: they premiere at Telluride or Toronto or New York in September, and then are slowly rolled out in October, November, and December.

Sam Rockwell, Frances McDormand, Martin McDonagh and Graham Broadbent at the Toronto International Film Festival for Three Billboards Outside Ebbing, Missouri

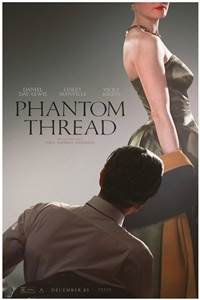

2017 is no different: right now, depending on which Oscar prognosticator you read, at least seven of the possible Best Picture Oscar nominees were released, or will be released, within the last couple of months. The outliers are Christopher Nolan’s wartime thriller Dunkirk, Jordan Peele’s exciting directorial debut Get Out, and other dark-horse candidates like The Big Sick; Get Out, a safe bet to get nominated in a number of Oscar categories, would be the equivalent of The Silence of the Lambs, a horror film that hits the zeitgeist and was released in February. However, these are still outliers, where other likely nominees such as The Florida Project, The Post, Phantom Thread, Lady Bird, and Three Billboards Outside Ebbing, Missouri either went the traditional festival route, or are just now being unveiled to critics and industry audiences.

The Post and Phantom Thread might be the most extreme examples of the latter case. Steven Spielberg, in the middle of post-production on his upcoming sci-fi/adventure film Ready Player One, read the timely script for The Post, rounded up an all-star cast including Meryl Streep and Tom Hanks, filmed the movie, and finished it all within the last 12 months, barely without breaking a sweat. Paul Thomas Anderson’s new film about a fashion designer in 1950s London also began filming this year, and was too far into post-production in the fall to be unveiled at festivals. The studios distributing these films were no doubt all too pleased to wait until December to unleash new films from such beloved directors during the holiday season.

Racing Against the Clock

From the perspective of a critic, this is both a good and a bad thing. It is, generally speaking, a wonderful gift to know that the last quarter of a calendar year will be the home to many exciting, challenging, and unique movies. In a year like 2017, movies like Dunkirk, Get Out, and The Lost City of Z thus feel like pleasant surprises, lined as they are throughout the rest of the year. The flip side is that the last few months of 2017, or other years, become improbably busy for a diligent critic, just to make sure that you’re as up to date as possible with the most lauded films from big and small studios. It would be wrong to complain too much about this problem—woe is the film critic, struggling to watch a lot of movies in only a couple of months—but the choice that studios make to backload their higher-quality films at the end of the year still causes problems.

Look again at the 2017 release schedule. The first three months of the year only featured three movies that are likely to be honored, even with nominations, at the forthcoming Oscars. Two of those are animated films—The LEGO Batman Movie and The Boss Baby—and are likely only going to get Best Animated Feature nods. The next contender of any kind opened in early June: Warner Bros.’ first good DC movie since the era of Christopher Nolan’s Batman, Wonder Woman. (The muted reception to Justice League may have done enough to kill Wonder Woman’s chances at any Oscar buzz aside from VFX nods.) The summer also featured The Big Sick and Dunkirk, but was otherwise light on anything other than bloated sequels, unnecessary franchise revivals, and unwanted adaptations of dubious source material.

This is not a screed that’s meant to suggest that 2017 was a bad year for movies. 2017, like pretty much every year, has been a great year for movies. The diversity of storytelling, the further diversity of the people getting to tell those stories, and the generally exciting feeling of watching new films from auteurs like Spielberg, Nolan, Anderson, James Gray, Dee Rees, Patty Jenkins, Peele, and others has made this a phenomenal year for film. But every December (at least within the last decade or so), the feeling is less that it’s been a great year for movies, so much as a great three months for movies.

Peak Movies?

If you read any amount of TV criticism these days, you’ll likely see critics rightly point out the frustrating fact that there’s simply too much TV to watch and keep up with these days, on countless networks, platforms, and the like. Each week, Netflix has a new TV show or stand-up special, and the same kind of frequency can be found both on networks as well as the countless cable channels and online platforms available to viewers around the world.

That kind of frequency isn’t yet overwhelming the world of cinema. The last four calendar years have each featured at least 700 movies released around the United States, but just over 250 of them were released in at least 100 theaters at any point in their release. The point is this: if there are only so many movies getting even a mildly large release strategy in a given 12-month period, why are so many of them cramped into the last few months of the year?

Though the Oscars have found more favor in recent memory with films that aren’t massively popular—the last four Best Picture winners have an average box office gross of $43 million, and The Hurt Locker is the lowest-grossing Best Picture winner in the last 40 years at just $17 million—studios still assume that placing awards-bait movies earlier in the year is a sure guarantee that they’ll be forgotten. Both Get Out and Dunkirk were box-office successes, but each of them has stuck around so long in the awards conversation as much for their popularity as for the way they speak directly to the current political and societal moment in America. Smaller films may have been critically well-liked but can’t stand themselves apart from the rest of the pack. So it’s a vicious cycle: studios see their movies get forgotten in the early part of the year, so they shove them in November and December, in the hopes that they won’t get forgotten in the late part of the year. It’s a gamble either way.

The patterns of how studios release their movies shift gradually; only ten years ago, Warner Bros. took the gamble of releasing a big-budget action film in March, and once 300 proved a big success, it inspired other studios to begin taking those kinds of leaps as well. Now, the summer movie season is nearly an all-year sport, with only a couple of months representing the quiet periods. Should movies like Dunkirk and Get Out prove successful at the Oscars, maybe it will help reshift studios’ perspectives regarding whether or not they can risk releasing a prestige picture outside of the late fall and early winter. They’re overdue to start spreading the cinematic wealth.