by Monte Yazzie

You can learn a lot by listening.

As a teenager who would hang out at the local record store, the corner bookstore, and the video rental store on a consistent basis, I began to hear the random banter of store clerks passionately defending the best album of 1993, the seminal author of the last fifty years, or the greatest films in the history of cinema.

These encounters led me to music, literature, and film that were far outside of my maturity level at the time, like my utter confusion at 15 years old with Stanley Kubrick’s “2001: A Space Odyssey” or the jaw-dropped look on my face at 17 after watching Alejandro Jodorowsky’s “El Topo”. To say that these films left an indelible impression on me would be an understatement. Fast forward nearly twenty years, and I still find myself listening in the middle of conversations, some onlookers may call them arguments between impassioned film critics either defending or attacking the validity of what was just screened.

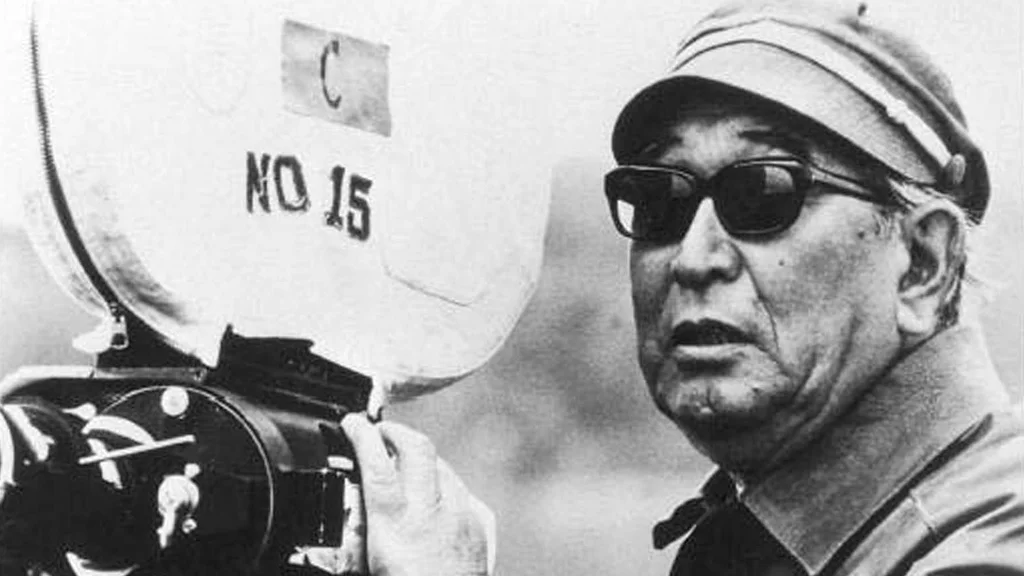

Still, there are some films that reach the realms of “sacred territory”, and there are some filmmakers who, regardless of what their film may be about, are immediately granted the “must watch” label. It’s hard to question the validity of filmmaker Akira Kurosawa, a genius Japanese filmmaker who is responsible for many of the technical film forms, character compositions, and narrative structures seen in contemporary cinema and within works from acclaimed filmmakers like Martin Scorsese, Quentin Tarantino, Ingmar Bergman, Francis Ford Coppola, Sam Peckinpah, Steven Spielberg, and George Lucas. Or, as a film-loving friend of mine once proudly exclaimed, “Kurosawa is your favorite director’s favorite director”.

Mr. Kurosawa tackled numerous genres of film with fearless enthusiasm, starting his career with the character-driven martial arts saga “Sanshiro Sugata”, the noir-driven “Stray Dog”, and the war-time relationship drama “No Regrets for Our Youth”; these superb films all arriving before the monumental acclaim of the film that would make Mr. Kurosawa an internationally recognized auteur. Looking into the five different decades of Kurosawa’s film career will display a filmmaker who excelled in every aspect of the filmmaking process and a director who always sought to tell stories in innovative, inventive, and intriguing ways until the end of his career. While it would be easy to look at the films that have defined this legendary filmmaker’s career, “Rashomon”, “Seven Samurai”, “Ikiru”, “Sanjuro”, “Yojimbo”, “High and Low”, and “Throne of Blood”, I think it is interesting to look at where filmmakers of Mr. Kurosawa’s caliber started and where they ended.

The Beginning: 1943 - 1950

Akira Kurosawa began making films at the age of 26, working mostly as an assistant director. Young Kurosawa learned the process of filmmaking by working with one of Japan’s leading filmmakers, Kajirō Yamamoto. Many of Mr. Kurosawa’s early works were made during World War II, and the influence of the war can be felt throughout much of his early work, which sways heavily into structures of propaganda.

No Regrets for Our Youth

Postwar Kurosawa allowed more freedom for the filmmaker; look no further than his first film after the war to feel the director’s criticism of Japan’s involvement. Kurosawa did this with a story about a young girl struggling with life and love in the shadow of uncertainty for her country which is on the brink of entering a war. The film, “No Regrets For Our Youth”, also boasts one of Mr. Kurosawa’s only female protagonists in the exceptional performance of Setsuko Hara who plays a transforming young woman named Yukie.

Drunken Angel

All of these early steps were leading to the highlight film of the 1940’s for Kurosawa. In his amazing career catalog, the 1948 film “Drunken Angel” often times gets under-appreciated. This melodrama places two unlikely characters, a cynical alcoholic physician and a handsome mobster suffering from tuberculosis, in an awkward relationship that moves into something more complex than what is displayed on the surface. While at the core of the story is the common theme of good versus evil that would continue largely throughout Mr. Kurosawa’s entire career, the film creates something more multifaceted out of the relationship between these two men. Underlying themes of honor and sacrifice motivate both men into action but also promote changes that display the postwar sentiments felt by those looking to change the mentality of the past for Japan. It’s a fascinating relationship when analyzed through this lens of the culture at the time.

Takashi Shimura, who plays the boozing physician Sanada, exceptionally composes the character. Mr. Shimura is at one point unredeemable only to turn at another point in a completely different direction that makes his character filled with honor and esteem. It’s a complicated composition that Mr. Shimura deftly handles. “Drunken Angel” is often known for bringing Mr. Kurosawa and longtime acting collaborator Toshirō Mifune together for the first time. The team would eventually go on to make 16 films together throughout Mr. Kurosawa’s career. Mr. Mifune’s undeniable charisma and authority can be felt the moment he arrives on screen in this film as the ill mobster Matsunaga. The performance displays the power that Mifune can deliver just by walking on screen or uttering a line of dialog. With the mobster the actor builds a convoluted character, one that can see his ultimate fate and struggles to follow a code of honor that will display the weaknesses that he is trying to hide. These characters display Mr. Kurosawa’s ability with working a script; he forms these characters from simple representations into sincere characters challenged with difficult choices. The director would continue to demonstrate this ability as his career matured.

Rashomon

“Rashomon” is a film adapted from a short story by Ryûnosuke Akutagawa. It was the masterpiece that made the world pay attention to the Japanese auteur. The 1950 film details a single incident, the murder of a samurai and the possible rape of his wife, through the flashbacks of four different perspectives. It’s a mystery, a story that manipulates the truth. This theme of the perception of truth will also continue in different ways throughout his career.

From a technical perspective, this film was a painstaking effort for Kurosawa to complete. It’s a perfect example of the director’s uncompromising dedication to the vision he established. Kurosawa would wait until the natural lighting was perfect for the scene, he would also utilize the surrounding natural settings to build crucial elements fundamental to the film, everything was in the details. Take for instance one of the best scenes when a moving camera follows the mystery of the story into the woods. The use of ambient sound, the score written by Fumio Hayasaka, the editing structure, and the ingenious imagery combine to create a silent moment that speaks volumes. It would not be long for the world to take notice, as the movie would reawaken the world to Japanese film at the Venice Film Festival. It would continue to impress as it won the Academy Award for Best Foreign Language Film.

“Rashomon” challenged the way filmmakers were making films; it brought Japanese film to a new realization of possibilities and levied an expectation for Mr. Kurosawa’s next and later works.

Ran

The End: 1985-1993

In 1985, Mr. Kurosawa crafted another masterpiece with the film “Ran”, an interpretation of William Shakespeare’s “King Lear”. “Ran” is a grand spectacle, beautifully photographed to the point of being almost overwhelming; the film is influenced by everything Mr. Kurosawa did before it. From the sweeping samurai sagas to the complicated human dramas, the film is a constant metaphor for the changes of culture and political landscapes but also for Kurosawa’s life as an artist. You can feel the contemplation of the past but also the insecurity for the future, both for him and for the art. It’s a darker film unlike many in his catalog. This late career film of Kurosawa, who at this point in time was intermittently making movies, is at times pessimistic and cynical, a call back to the structure of an early character of the physician Sanada in “Drunken Angel”. Everything that has composed the samurai sagas for Mr. Kurosawa’s career is here, but it’s more honestly brutal and sided towards the worst characteristics in people.

In medieval Japan the elderly warlord Ichimonji is retiring, he is turning over power to his three sons. However, power comes with temptation and corruption and Ichimonji’s youngest son Saburo knows this and disagrees with the decisions of the group. Saburo is banished and control is given to the older sons, Taro and Jiro, who become selfish with power that leads them to broken promises and war. It is up to Saburo to save his family.

“Ran” is just one example of the incomparable filmmaker contemplating the future, much of the films made after 1985 have this deliberate theme in place. Working with symbolisms and metaphors to make personal statements about different philosophies, life lesson, and world perspectives completely inundated much of his late work. Kurosawa knew that with each new film it had the potential of being his last and final film. The director would become more intentional and thoughtful with his work, painstakingly planning out every scene with great detail. The intricacy is on full display in “Ran”.

Mr. Kurosawa is responsible for creating many of the camera movements, edits, and choreography seen in modern action cinema. The filmmaker placed the viewer into the middle of the action, dashing and sweeping across the screen with the actors and deliberately cutting the scenes to feed the appetites of the viewer with moments peaked with powerful anticipation and exhilarating payoff. However, in “Ran”, the style is different from his past work. The world is bigger, instead of showing the intimacy of battle, Mr. Kurosawa pulls the camera back and displays the world embattled and a humanity that is destroying itself. It’s a scenario that doesn’t try to showcase style but is still packed with substance from an artist trying to explain a perspective from his mind with images. It’s brutal and bold and beautiful.

This wasn’t the end for Mr. Kurosawa. Three more films prevailed after “Ran”, a personal fairy-tale that composes a majestic collection of Japanese folklore and the actual sleeping visions that Mr. Kurosawa encountered in the film “Dreams”, the heartfelt memories of an elderly woman struggling with the past and its effects on the present in “Rhapsody in August”, and one of the most poignant farewell films from any filmmaker in the tribute to Japanese writer, educator, and national treasure Hyakken Uchida in “Madadayo”.

In these final films, Mr. Kurosawa provides an insight into what is important to him as a person but also what was and is important to him as a filmmaker. He continued to compose brilliant imagery that was both realistic but also, unlike some of the middle-career earlier work, far more fantastic and filled with bold brush strokes from his imagination, such as many of the scenes composed during the stories in “Dreams”. These films display his political point of view with steadfast honesty. The contemplations of the government’s involvement in matters of war that distinctly emphasized themes in his early work in subtle ways are so much more defiantly and purposefully structured without words in his later work, for example, the pain of Hiroshima and the image of a playground’s melted jungle gym in “Rhapsody in August” speaks volumes.

Still, even though these latter works speak and compose subjects and characters that are different in tone than his early movies, in the director’s final film Mr. Kurosawa displays that characters are powerful tools capable of promoting significant change by simply providing an opportunity for someone else to experience happiness. Try and keep from smiling when you realize that one of the most influential and arguably one of the greatest filmmakers titled his farewell film “Madadayo” which when translated means “not yet”. The legacy of this master still lives on.

Seven Samurai