by David Appleford

There’s a story regarding Rock Hudson at a film premiere at the Pantages Theatre on Hollywood and Vine in 1968. Some say it’s a movie-myth, but film critic Roger Ebert was there and he wrote about it -- 241 people walked out of the theater before the film’s conclusion. Among them was Rock Hudson, who declared aloud while exiting down the aisle, “Will someone tell me what the hell this movie is about?”

The film in question was Stanley Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey.

2001 at 50!

This year marks the 50th anniversary of the sci-fi classic. To celebrate the occasion, an unrestored 70mm print made from original negatives –- nothing digital added, no tricks, nothing remastered, and no new edits to revise history -– will debut May 12, 2018 at this year’s Cannes Film Festival. It will have an introduction from someone who was not even around when the bewildered Hudson made his exit 50 years earlier. Film writer and director Christopher Nolan, who oversaw the production of the new print, has said that presenting the film is, “an honor and a privilege.”

After the Cannes presentation, the film will open in select theaters May 18, 2018 followed by new releases of the restored version on DVD, Blu-ray, and 4K Ultra High-Def later this year. Those who know what Cinerama is and what the film looked like on that giant, curved screen should be chomping at the bit.

A Film By Any Other Name...

While 1968 was the year of the film’s release, things actually began in 1965. On Tuesday, February 23 of that year, MGM studios issued a two-page typed release to the media announcing its plans for a new Stanley Kubrick project that was due to start production on August 16. It was to be filmed in the giant Cinerama process and called Journey Beyond the Stars.

Privately, once MGM gave the greenlight on Cinerama, Kubrick and writer Arthur C. Clarke called their film How the Solar System Was Won, a joke referring to MGM’s previous Cinerama blockbuster, How The West Was Won. In reality, Journey to the Stars was never going to be used. The first working title was Voyage Beyond the Stars, but when the sci-fi thriller Fantastic Voyage was released, Kubrick is said to have disliked the Isaac Asimov penned adventure so much, he changed the working title of his own film from Voyage to Journey... not that it mattered.

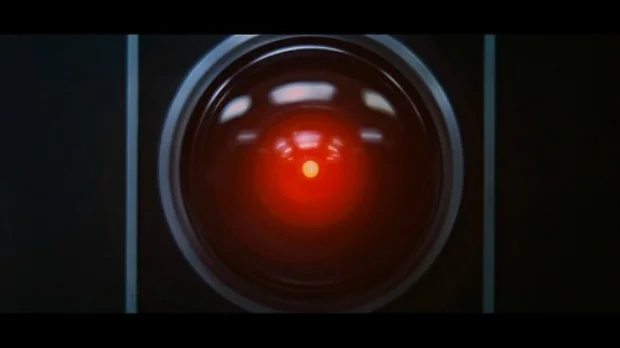

The final title that Kubrick decided upon was never going to be quite so ‘B movie' obvious. It was based on two things: the futuristic year was chosen from what would be the first year of both the 21st century and the 3rd millennium, while the subtitle would be culled from Homer’s The Odyssey. Thus 2001: A Space Odyssey it was. And like Homer’s Greek poem of an epic journey, Kubrick even had his own one-eyed Cyclops to battle along the way; the computer, Hal 9000. Plus, just for the fun of it, if you enjoy comparing, contrasting, and connecting the dots, consider the following. Homer’s hero, Odysseus, was a legendary bow man. Kubrick’s central figure played by Keir Dullea is called David Bowman. Coincidence? Knowing the director’s exhaustive research on any given subject, in the world of Stanley Kubrick, there are no coincidences.

The Production Begins

Kubrick had previously moved his family from New York and settled in a house on the outskirts of London where he made his films. The film was planned for a two year production schedule at London’s Shepperton Studios. Then, the production would move on to the MGM-British Studios in Borehamwood, all at a cost of $6 million, a staggering figure in 1965.

There were lots of cuts and changes throughout both the writing and the filming process. The original Stanley Kubrick and Arthur C. Clarke working script had a full voice-over narration that basically spelled the whole thing out. Had Kubrick kept to the original outline, you would have heard a narrator explain towards the end of the film, “Now, the long wait was ending. On yet another world, intelligence had been born and was escaping from its planetary cradle. An ancient experiment was about to reach its climax.” But as production continued, Kubrick cut and cut to the point where virtually nothing was explained. It was down to the visuals and our interpretation of them.

Another cut occurred during the final seconds of the film. Earlier, when the story jumps from the Dawn of Man to the year 2001, those space crafts we see circling the Earth to the opening chords of The Blue Danube are not ships at all; they’re nuclear bombs, weapons sent into space by various powers ensuring their protection from above. During the final sequence when the Star Child floats back to Earth, as in the Arthur C. Clarke’s novel, those bombs are ignited and rendered useless, one by one, until there’s nothing left. Unfortunately, having just ended Dr. Strangelove in a similar fashion, Kubrick didn’t want to be perceived as copying himself, so he made another cut. Had he left the sequence alone, at the very least, it would have given the film an undeniably spectacular ending.

What was originally supposed to be a late 1966 release ended up taking longer to film than planned. Eventually, 2001: A Space Odyssey was completed after three years in the making with an eventual cost of a studio back-breaking $10 million, plus.

And if that wasn’t tough enough to make the studio execs break into a sweat, once they saw a preview of the film, the end result looked so… well, confusing. What happened to the traditional three acts? Where was the beginning, middle, and end? For twenty minutes or more there wasn’t even dialog in the first part, nothing of importance said in the middle, and as for the finale, the execs were just as puzzled as Rock Hudson was going be, along with the other 241 attendees who marched out of the LA premiere.

A Critical Response

For the most part, critics were equally perplexed. Among the notable names of the sixties, New York magazine’s John Simon called it, “a regrettable failure.” Andrew Sarris wrote, “it was one of the grimmest films I have ever seen.” Stanley Kauffmann called it, “a film so dull, it even dulls our interest in the technical ingenuity for the sake of which Kubrick has allowed it to become dull.” And worse, Pauline Kael in her Harper’s magazine review slammed the film, writing that it was, “a monumentally unimaginative movie,” likening its length to the oversize ego of its creator. Kubrick is said to have been deeply upset with Kael’s observances.

But not everyone thought the same. The Boston Globe called it, “the world’s most extraordinary film.” The Christian Science Monitor wrote that it was, “a brilliant intergalactic satire on modern technology.” The New Yorker’s Penelope Gilliatt described it as, “an unforgettable endeavor.”

A Studio Shuffles

MGM was baffled. Once it opened, box-office wasn’t doing the business required to recoup the monumental costs, so the studio made plans to cut its losses. It intended to remove the film from its curved 70mm screens to make way for an early release of another of its Cinerama movies, Ice Station Zebra, a film with a more conventional beginning, middle, and end, and even starred the previously befuddled Rock Hudson. But theatre managers were noticing something odd occurring.

A young generation of movie-goers were continually buying out the first few rows of the theatre, getting high, and immersing themselves in the images, particularly the psychedelic journey of the final 20 minutes. Realizing it was a trend that was growing, managers begged the studio to reconsider pulling the film. Give it time, they requested; there’s something happening. The pause paid off. Tripping audiences made return trips. Plus, they were spreading the word and tickets sales climbed. Soon, theaters were packing them in. By the end of the year, 2001 was the highest grossing film of ‘68.

Part of the problem that threw MGM’s box-office rhythm out of whack was the lack of advanced sales for the separate performance roadshow presentations (theatres that ran the same film for lengthy periods). Unlike today, during the sixties, films were rarely kept alive by the attendance of teenagers. They didn’t use credit cards, and they didn’t book things in advance; they would turn up on the day and pay cash. The studio couldn’t make decisions based on the purchase of future tickets, because there were none.

You’ll often hear it is said that 2001: A Space Odyssey changed the way sci-fi films were made. You can also say, it changed the way all films were sold. Young audiences in 1968 kept returning. Even John Lennon is quoted as saying in ‘68 that he saw the film at least once a week. Plus, there were other influences. The fictional astronaut David Bowman inspired a certain singer/songwriter to change his name from David Robert Jones to David Bowie when he released his sixties pop/rock classic "Space Oddity".

2001 in the 2010s

So, now, fifty years on and a newly minted 70mm anniversary edition about to be unleashed, what’s with all the hoopla? Is the film worth it? Is it just as relevant? Does it still feel inspirational? And is that final act any easier to understand? Yes. Absolutely. Beyond a doubt. But if you’re new to the film, probably not. However, go on-line, search around for the endless array of 2001 amateur blogs and professional websites and you’ll find plenty of well crafted essays happy to tell you what the film is all about.

Many of the more recent critiques you may read from those who weren’t around in 1968 and have only caught the film in the last decade or so may talk in terms of how slow the film is, or how individual shots seem to last forever, as if there’s something wrong with that. Certainly by today’s low attention-span standards, 2001 is practically pedestrian. But what those youthful pundits fail to consider is the time of the film’s release and its Cinerama presentation.

When 2001 opened, there was no other movie that had ever given the opportunity of looking at what appeared to be the sight of something real floating in space, or how the Earth really looked from afar. It was eye-popping. The visual effects of Douglas Trumbull were the first of their kind, and remain spectacular today. To rush the sight of a craft on its way to a circular space station with cuts and fast-paced edits just to keep things moving and to maintain the attention of the young is to lose the grace and rhythm of what is occurring. Plus, the sheer size of the image, particularly if you were lucky enough to see a 70mm print or a fully-fledged Cinerama presentation, allowed your eyes to explore all corners of the screen and to take everything in at your own pace, as you would in real life; a luxury rarely afforded in today’s cinema.

If the chance to see ‘2001’ in its new 70mm print comes your way, then take advantage. Sadly, outside of LA and Seattle, there’s little chance of catching it on an authentic Cinerama screen - for those unfamiliar, think IMAX, but wider and deeply curved - but if there’s a 70mm presentation nearby, hunt it down and stand in line. The clarity will stun.

Interestingly, even though the film is 142 minutes long, there are only 40 minutes of dialog. And most of what is said consists of nothing more than everyday pleasantries rather than plot. Yet there is one scene of major importance spoken just before the final act, and it puts everything into perspective.

When astronaut David Bowman unplugs most of Hal’s higher logic modules, a specially recorded video message from Dr. Heywood Floyd (William Sylvester) back on Earth is suddenly played on a nearby monitor, one that was meant to be seen by every crew member, but now can only be seen by the sole, surviving Jupiter Mission voyager. And even though there may still be twenty minutes of film left to go, that prepared speech relayed on the video monitor are the last words you’ll hear. It’s just a few sentences, but they’re haunting.

“Eighteen months ago, the first evidence of intelligent life off the Earth was discovered. It was buried forty feet below the lunar service, near the crater Tycho. Except for a single, very powerful radio emission, aimed at Jupiter, the four million year old black monolith has remained completely inert. Its origin and purpose still a total mystery.”

And finally, here’s where things get personal. Whenever sitting around with a bunch of movie buffs, waxing philosophically about life, the universe, and everything, including inspirational films and favorite scenes from favorite movies, when it circles to me, I have a speech, and it’s this:

Picture the scene. Astronauts David Bowman (Keir Dullea) and Frank Poole (Gary Lockwood) sit secluded in one of the space pods. There’s something wrong and it needs to be talked about, but in private. They switch off all radio communications so that they can’t be heard by their computer Hal 9000. Once completed, the two men proceed to discuss the computer’s fate, including shutting it down to its most basic level. They think they can’t be heard, and they’re right; Hal can hear no sound. But he can observe. What the astronauts don’t know, and it’s something that’s revealed to us from the computer’s point of view, is that Hal can see the two men through the small, oval-shaped window of their space pod. He’s lip reading. Once that revelation is apparent, the film cuts to Intermission. No sound, no further information. Just a black screen with white lettering.

The effect was devastating. A genuine jaw-dropper. A moment that packed such an emotional wallop, you couldn’t help but gasp and catch your breath. And it was at that exact moment back in 1968 while watching the film at the Casino Cinerama Theatre in London, the same city where Kubrick lived and his masterpiece was made, when my attitude towards film changed. It’s only halfway through the story, but 2001: A Space Odyssey had already proved something to an astonished thirteen year-old whose heart was still wildly racing from the effect of witnessing a powerful scene, simply presented: Film is something so much more than mere entertainment.

To quote Kubrick: “If 2001 has stirred your emotions, your subconscious, your mythological yearnings, then it has succeeded.” In other words, when you finally see it, how you react will be as individual in the experience as the design of a falling snowflake -- no two can ever be the same. You may find a kindred spirit -- one who regards the film on the same level as you. And you may find yourselves agreeing on much of the film, but ultimately, more than any other major Hollywood studio picture, your initial response and the emotions you’ll feel will be yours and yours alone. It’s something unique.

There’s simply no other film like it.